Annex I - Incremental Costs Analysis of the Project:

Regional Program of Action and Demonstration of Sustainable Alternatives to DDT for Malaria Vector Control in Mexico and Central America

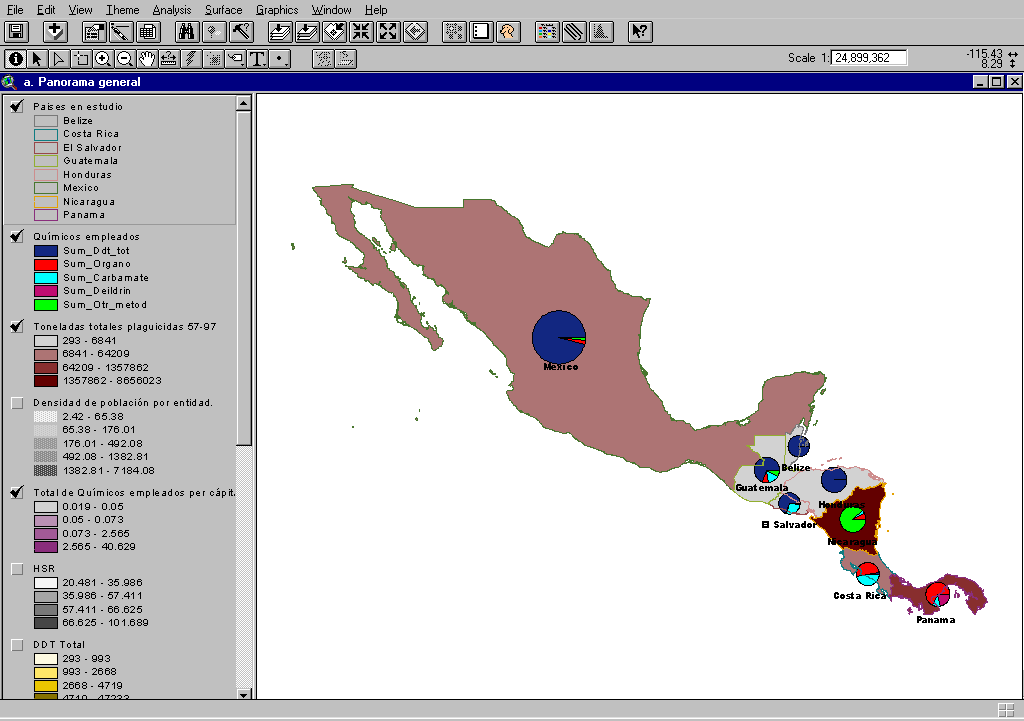

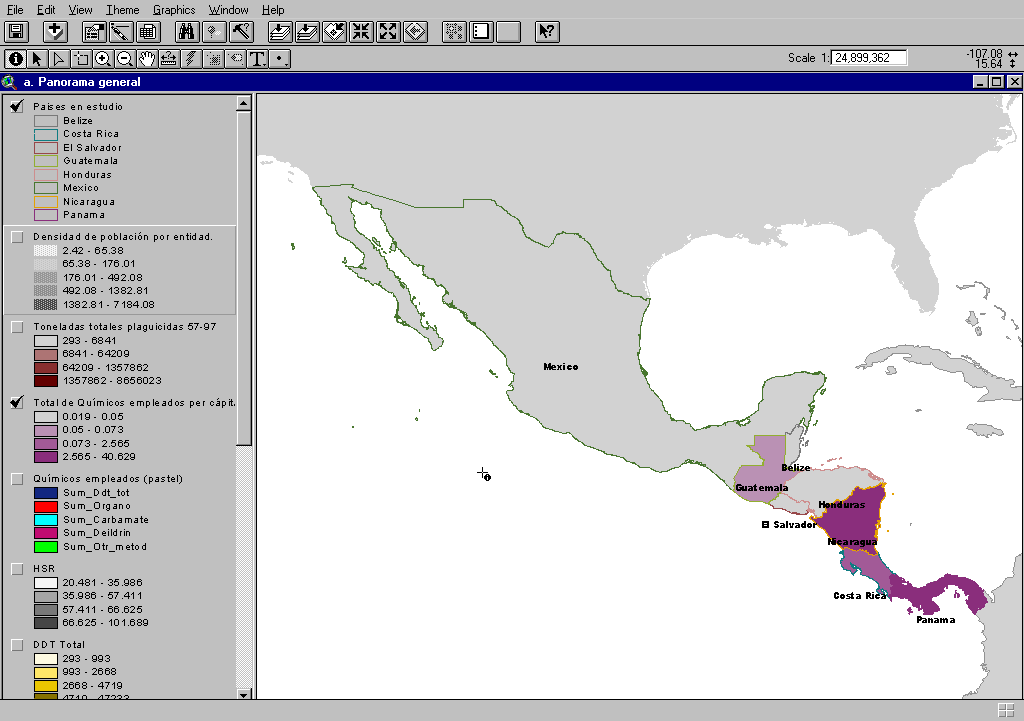

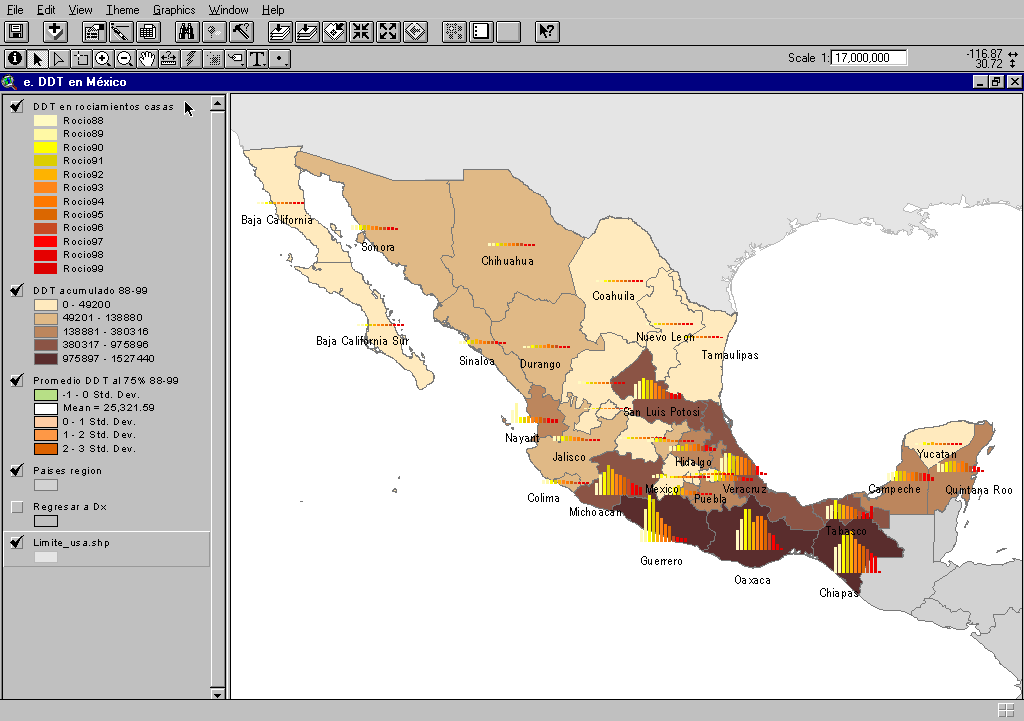

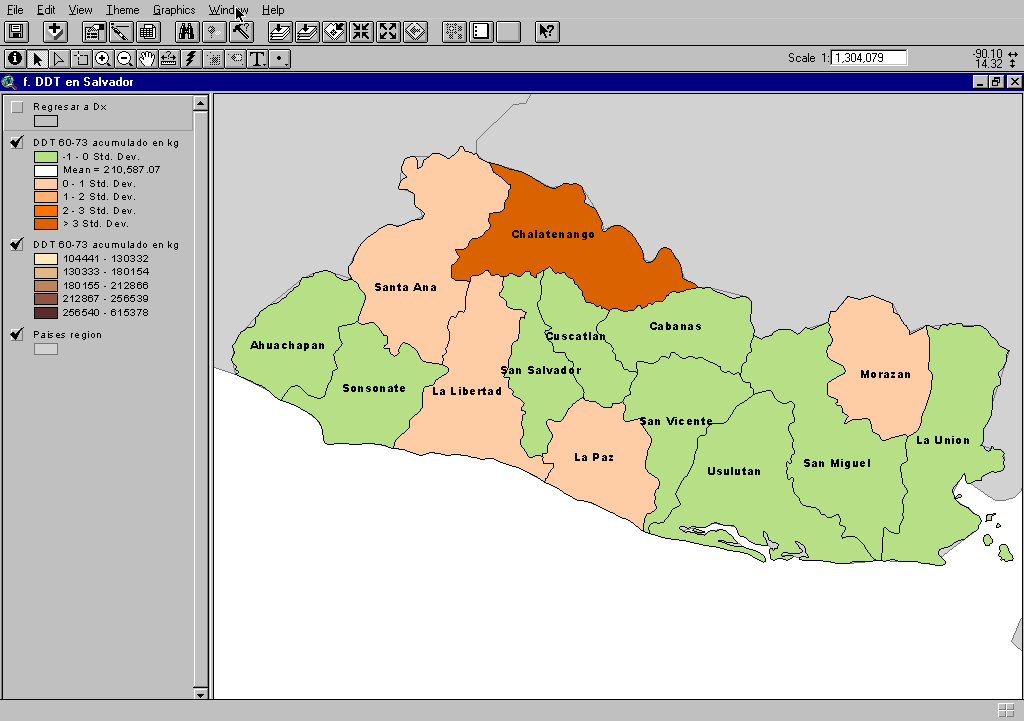

The overall objective of the project is to support the phase-out of DDT, globally, in a sustainable manner by validating and widely disseminating an array of alternative methods for malaria vector control that do not rely on DDT or other persistent pesticides. The project is to be implemented chiefly through demonstration projects in Mexico and the seven Central American countries - Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and Panama.

The analysis of the incremental costs attached to this intervention requires a discussion of the baseline and additional costs associated with achieving domestic and global benefits respectively. The regional scope of this project also requires a consideration of the regional benefits achieved through the intervention.

The global environmental benefits resulting from this project stem from the reduction of the releases to the environment of DDT and its metabolites. These are recognized global contaminants which have the capacity, once introduced in the environment, to persist for long times, be transported far away from point of origin, and bioaccumulate and elicit toxic chronic effects in biota, including humans. As the participating counties all border the Caribbean Sea, global benefits are also derived from the protection of its biodiversity and coastal resources from contamination from pesticides. Although the direct immediate global environmental benefits to be expected from the project will be relatively modest – resulting from the reduction in pesticide use in the demonstration areas and reduced risks posed by obsolete stockpiles of DDT, the mid to long term benefits will be much greater as the alternative methods validated by the demonstration projects are disseminated and replicated nationally in the participating countries, and globally. In addition to the benefits to the environment, human health benefits accrue globally from improvements in countries’ capacity to address malaria, resulting in reduced morbidity and mortality, as well as from reduced exposure of malaria control personnel and populations to DDT and other toxic pesticides.

Regional benefits that will accrue as a result of taking an integrated regional approach, in addition to the improvement of the quality of the environment, will stem from the greater emphasis placed on the mitigation of transboundary issues – from the better protection offered to temporary migratory workers to the mitigation of the risks of resurgence of malaria because of temporary weaknesses in the malaria control program of one of the countries.

National (domestic) benefits

The most immediate benefits resulting from this project at the national level will be mostly savings on the health systems resulting from reduced impact of malaria in the areas of demonstration projects. Indirect further benefits will result from the adoption and systematic replication of the best practices and lessons learned during the implementation of the demonstration projects. Greater public awareness about the hazardous effects of DDT compounds on environmental and human health will be an important tool to prevent reintroduction of DDT use in the participating countries. Other benefits will derive from: the incorporation of integrated malaria vector control principles into the existing framework of national health policies; the training of public health officers; the involvement and training of local communities in malaria vector control techniques; the elimination of the existing DDT stockpiles, the improved inter-sectoral collaboration, particularly between the health and environment sectors; and the strengthening of national health surveillance and pesticides monitoring systems.

Baseline Actions

All participating countries are engaged in national and regional actions to control the use of and risks from pesticides. One of such activities is the MASICA program and the PLAGSALUD project led by PAHO in the Central American countries, with support from the Nordic countries. This has already resulted in positive developments such as improvement of the surveillance and control of acute intoxication from pesticides, the revision of pesticide legislation, the establishment of local pesticide committees, and more specifically the improvement of the protection of malaria and other vector control personnel from exposure to pesticides. In particular, the national reports prepared during the PDF-B phase show that every country has been experimenting new and integrated approaches to malaria vector control during the past years. Mexico has been working on developing alternatives to DDT in order to phase-out DDT in a sustainable manner in the context of the North American Regional Action Plan on DDT. These activities contribute directly to the baseline on which the project relies by providing the set of tools that will be systematically applied, assessed, and validated. In addition, Nicaragua and Honduras have already disposed of their DDT stocks with international help.

For the purpose of this analysis, however, the only baseline costs that are considered in a conservative manner (as shown in Table 1) are the costs incurred directly by the participating countries (as well as PAHO and the CEC) in the implementation of project activities. The bulk of this baseline is represented by the redirection of the budgetary resources of the malaria control programs in the demonstration areas of each country. During the year of 1999, the national Malaria Control Programs of the 8 participating countries (according to governmental information provided to PAHO) spent the following amounts with the population of malaria risk areas, which is the basis for the estimate of a baseline contribution from the participating countries of US$ 5,026,000 to project component # 1 “Demonstration Projects and Dissemination:

|

Country |

Malaria Program (US$) |

Number of population in malaria risk area |

Cost per capita (US$) |

|

Mexico |

15,349,724 |

50,338,000 |

0.31 |

|

Nicaragua |

5,972,907 |

4,938,000 |

1.21 |

|

Panama |

783,700 |

461,000 |

1.70 |

|

Honduras |

388,956 |

5,667,000 |

0,07 |

|

Guatemala |

730,232 |

5,371,000 |

0.14 |

|

El Salvador |

3,307,167 |

6,154,000 |

0.54 |

|

Costa Rica |

2,664,000 |

1,332,000 |

2,00 |

|

Belize |

51,598 |

220,000 |

0.23 |

(Updated table for current malaria programs in Annex XX)

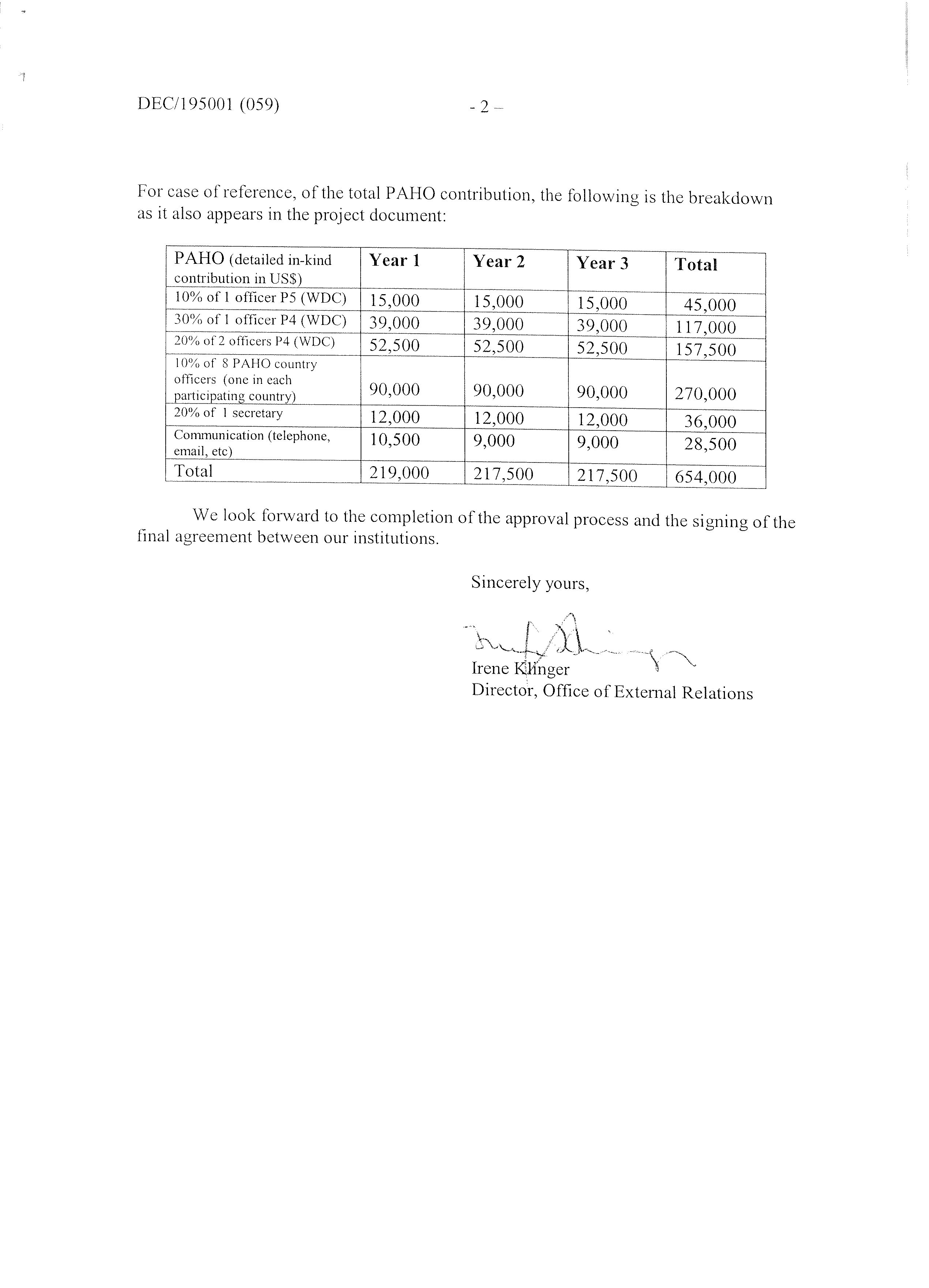

In addition, PAHO will support the project with an in-kind contribution estimated at US$ 654,000, representing the cost of technical assistance to the participating countries directed specifically to this project. CEC will contribute with US $200,000 for the assessment of DDT contamination in the environment and people in the areas of demonstration project in Mexico. The eight participating countries are committed to implementing this project as stated in the endorsement letters (Annex IV, X). Five of them have already signed the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants of May 2001. There is a regional willingness and preparedness to the adoption of techniques of vector malaria control which do not depend on DDT or other persistent pesticides. This project will however enhance the adoption of new vector control techniques by facilitating the transfer and exchange of experience between countries.

The GEF intervention is necessary to ensure that activities in the eight participating countries are coordinated and sustained. Indeed, without the GEF intervention, it is likely that countries will lack the capacity and the financial resources necessary to shift from an ad hoc testing of alternatives to DDT to their systematic application. Moreover, shifting the emphasis from the national/regional to the global level, the project will demonstrate that viable alternatives can be implemented that are safe, efficient, and cost-effective. Indeed, the bulk of the GEF financing is directed to project component No 1 “Demonstration projects and dissemination”. The project will add significantly to the baseline of national and regional activities by providing the participating countries the means to systematically and strategically validate alternative measures to control malaria vector, and assess, document, and widely disseminate the results.

Annex II - Logical Framework Matrix

|

Project Purpose: To contribute to protecting human health and the environment in Mexico and Central America by promoting new approaches to malaria control, as part of an integrated and coordinated regional program. |

|||

Overall Objective |

Objectively Verifiable Indicators |

Means of Verification (Monitoring focus) |

Critical Assumptions and Risks |

|

To prevent the reintroduction of DDT for malaria control in Mexico and Central America by demonstrating and disseminating techniques of vector control without DDT or other persistent pesticides, that are replicable, cost effective and sustainable. |

Malaria vector control programs in each of the eight participating countries adopt techniques of vector control that do not rely on DDT or other persistent pesticides. |

Regional Information Network with data on Malaria and DDT residues implemented and functioning. National health programs in Mexico and Central America are able to lower malaria rates by adopting new approaches for malaria vector control that do not rely on DDT. Raised public awareness on DDT hazards in environment, food chain and population prevents reintroduction of DDT for malaria control.

|

That the Governments of the participating countries will scale-up the methodologies used in the project and will apply them in the rest of the country, if proven successful. This seems likely in view of the strong support that this project has been receiving in the region. |

Outcomes |

Objectively Verifiable Indicators |

Means of Verification (Monitoring focus) |

Critical Assumptions and Risks |

|

Global level: New, affordable, cost effective and sustainable models for malaria vector control without DDT are tested in different ecosystems and geographic locations and can be replicated in other parts of the world. |

Nine replicable documented demonstration projects test a set of procedures for malaria vector control without the use of DDT or other persistent pesticides, under well identified environmental and social-economic conditions, during a 3-year period. |

Reports from each demonstration project result in a Case Study of procedures of malaria vector control without DDT tested for specific vectors, under different ecological and social-economical conditions. Technical manual of new techniques for malaria vector control.

|

That national governments and local authorities will accept the arguments put forward. The impetus created by the POPs Convention should ensure that other governments will be willing to adopt the process and design of DDT-free malaria vector control is likely. |

|

Regional level: Strengthened institutional capacities to control malaria with methods that do not rely on DDT. |

Regional network for sustained capacity building (laboratories, vector control technology, etc); and communication and information exchange among the participating countries (GIS, Web page, publications, etc). |

Information on new techniques for malaria control and databases related to the demonstration projects are available through regional network. Reference centers strengthened, laboratories validated and connected to network.

|

National governments are willing to exchange information, lessons learned, and results of their experiences of malaria control without DDT. Collaborative efforts initiated during the PDF-B augur well for this. |

|

National level: National institutions establish links between health, environment, and other sectors to ensure a sustainable and integrated approach to malaria vector control that relies on epidemiological surveillance systems, epidemic forecasting, detection of insecticide resistance, judicious use of chemicals and application of effective alternative control methods without DDT.

|

Malaria control programs in each of the participating countries shift away from reliance on DDT and consider alternative methods.

|

National Health Programs incorporate new methods of malaria control.

|

That the Governments of the participating countries are willing to adopt techniques for malaria control without DDT or other persistent pesticide. This is likely if demonstration is made of the availability of cost-effective alternatives. |

|

Local level: communities involved in demonstration projects are aware of new participatory and integrated techniques for malaria vector control and are aware of the hazards of exposure to DDT. |

Workshops held in each demonstration project site with the participation of community leaders and local NGOs. |

Report of workshops. Community participation section in methodology manual. Description of process and outcome of community participation in Demonstration Projects Case Studies and in final report. |

Local communities are receptive and are willing to collaborate and participate in the activities of each demonstration project. Experience shows this can be the case provided local communities are an integral part of project planing and preparation. |

Results |

Objectively Verifiable Indicators |

Means of Verification (Monitoring focus) |

Critical Assumptions and Risks |

|

1. Dissemination of information related to new techniques for malaria vector control. |

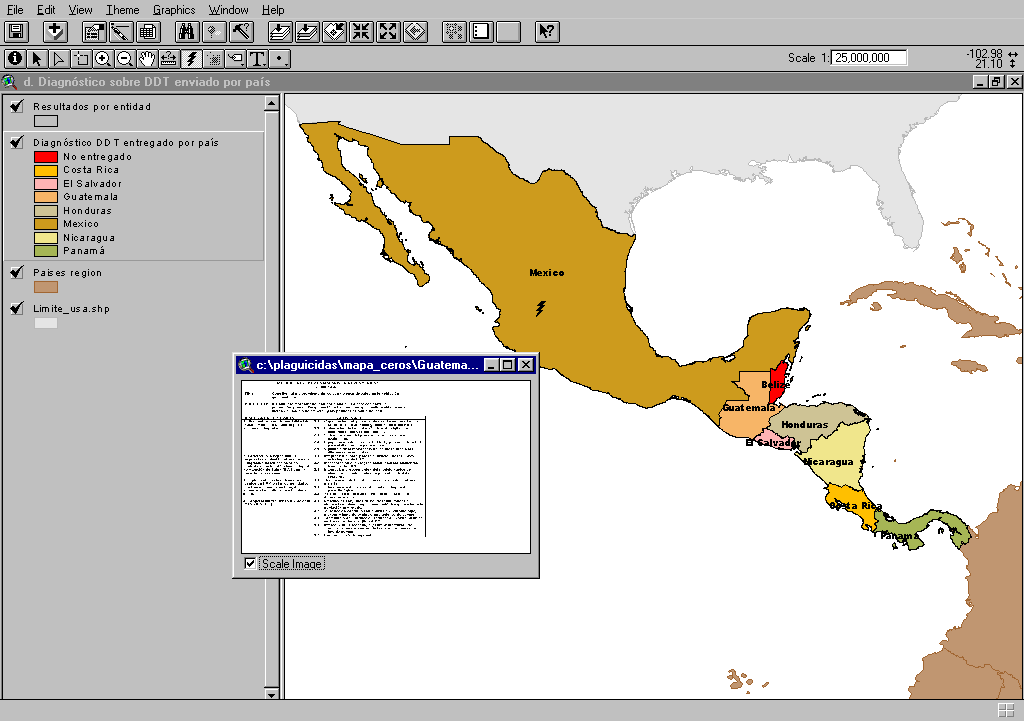

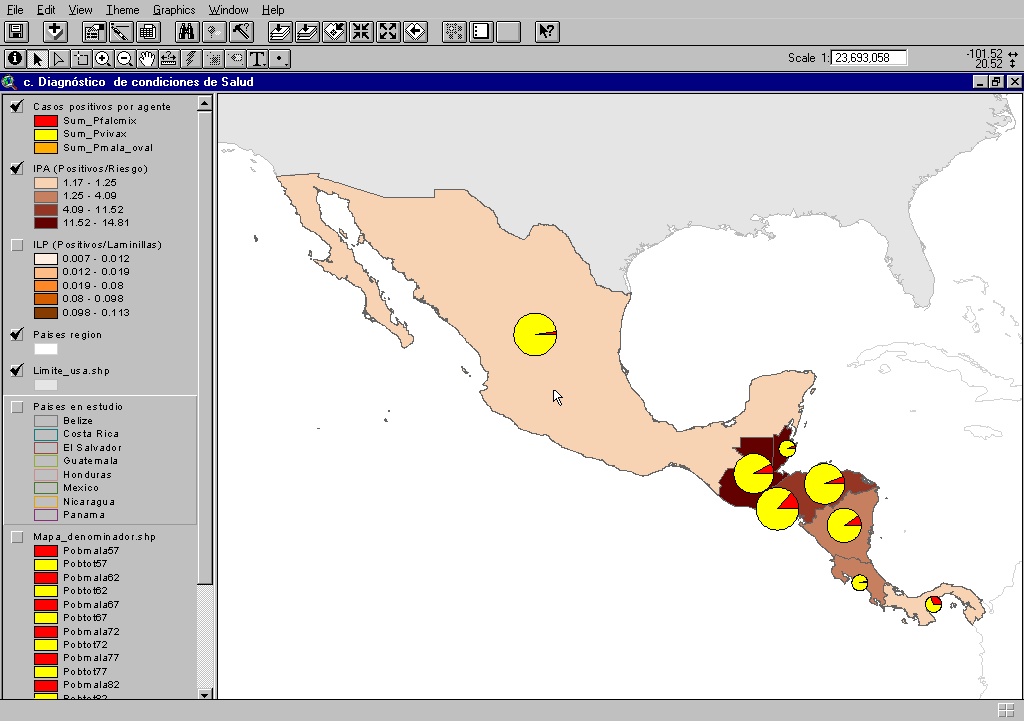

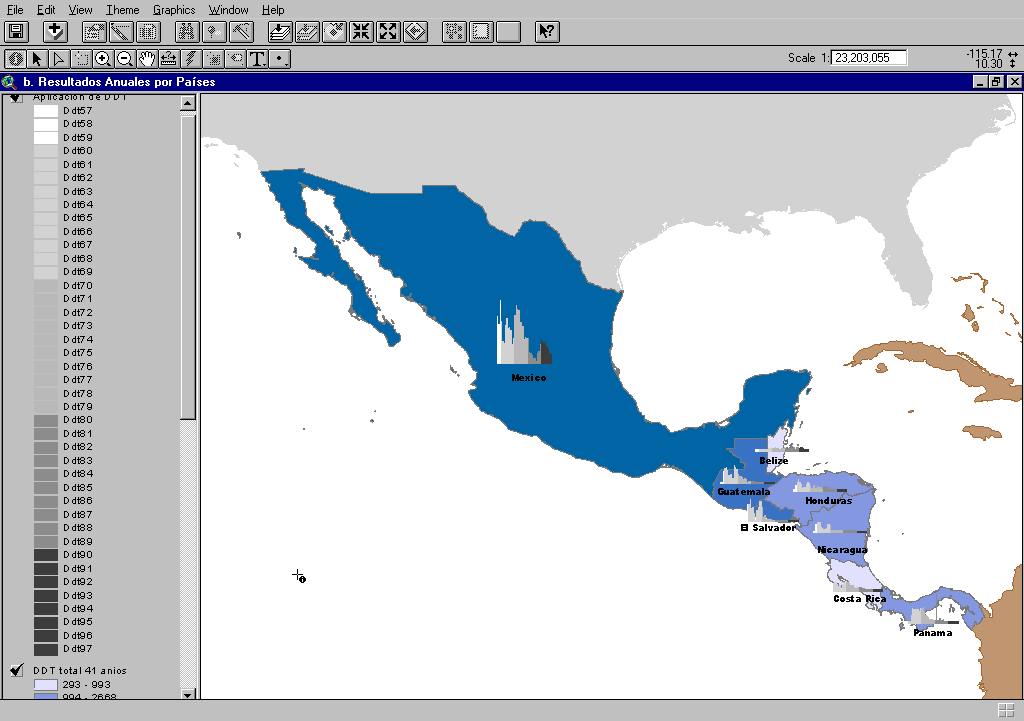

Region-wide information network on DDT and new techniques of malaria vector control (Web page, Intranet and GIS). |

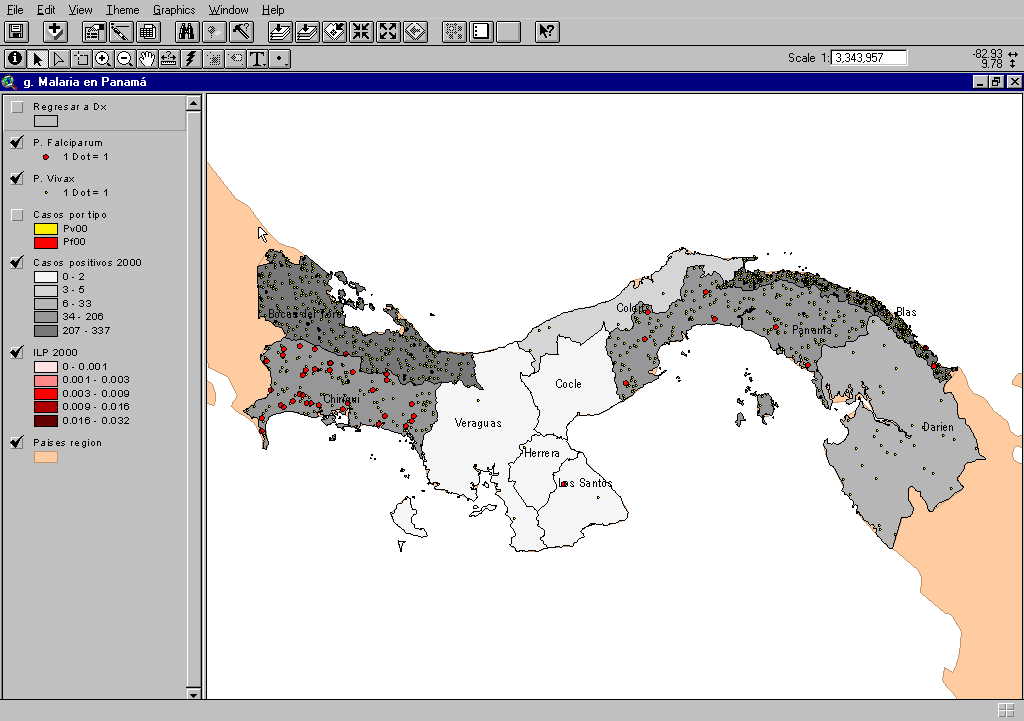

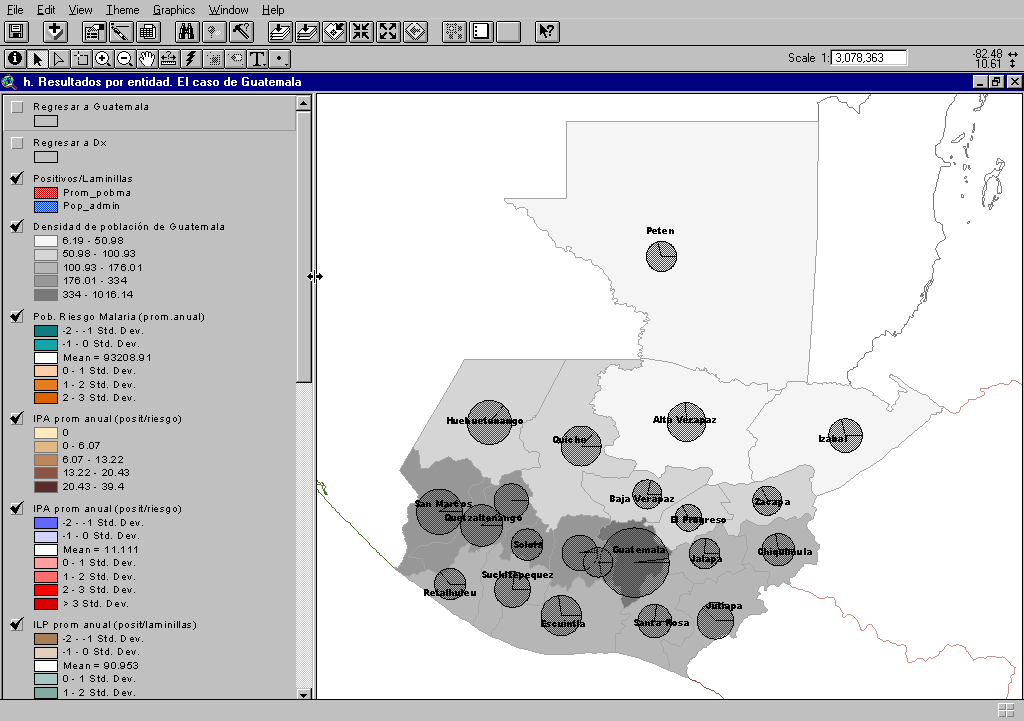

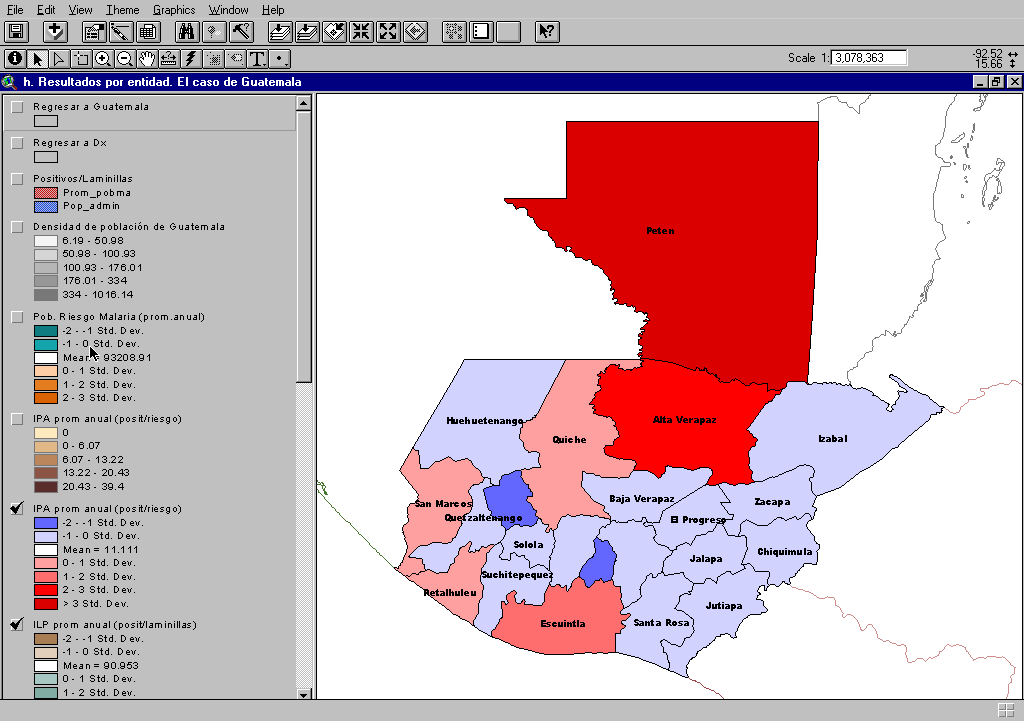

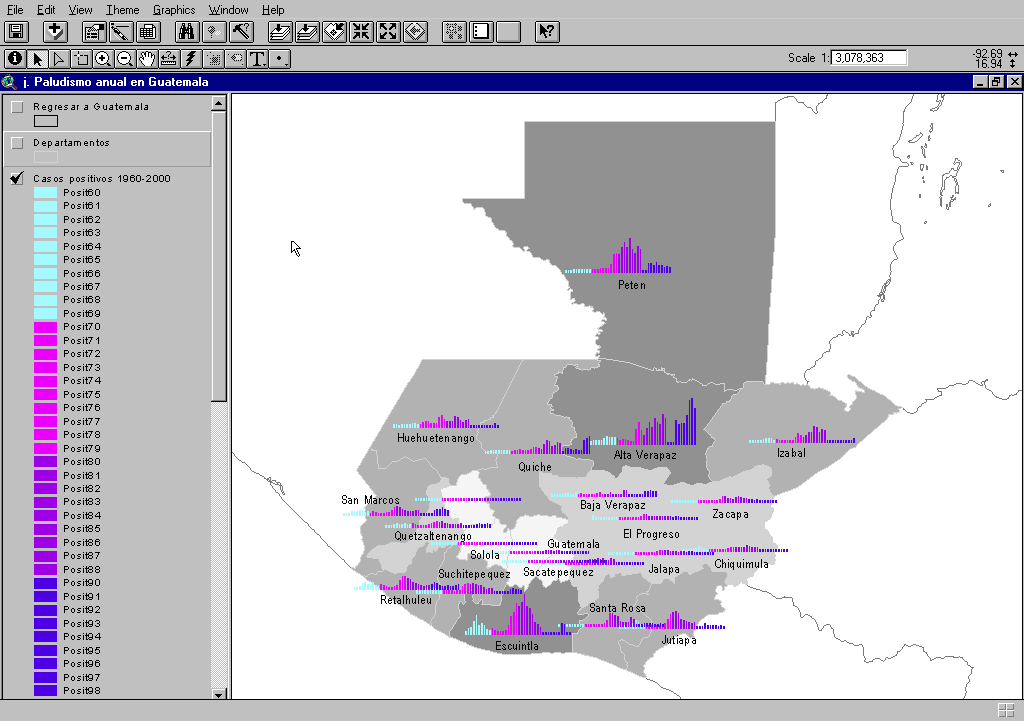

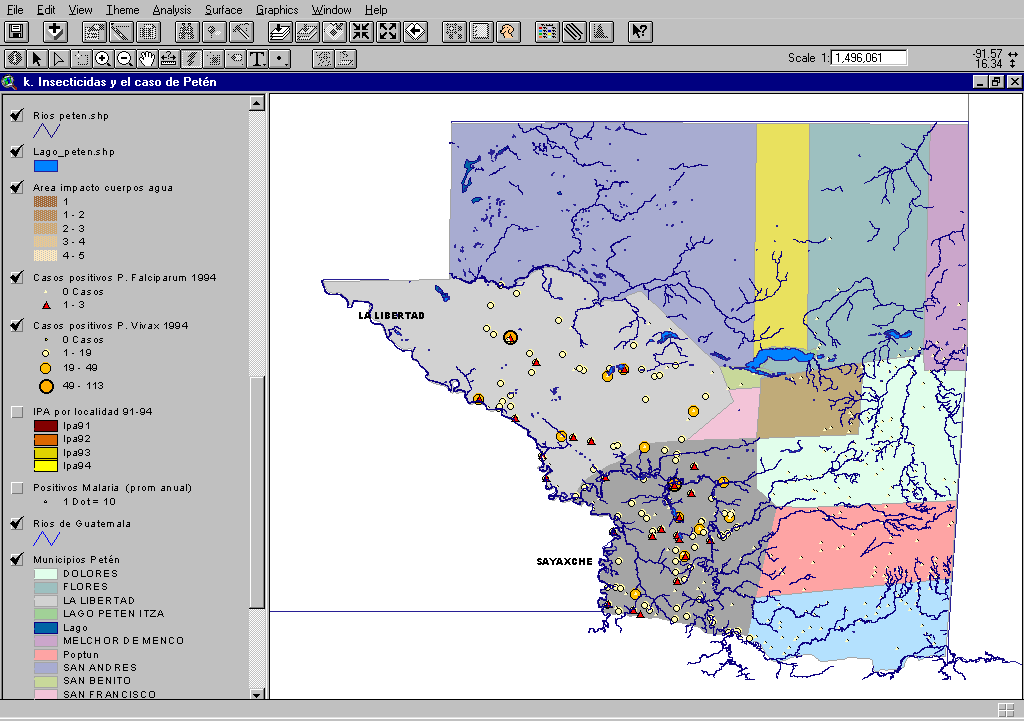

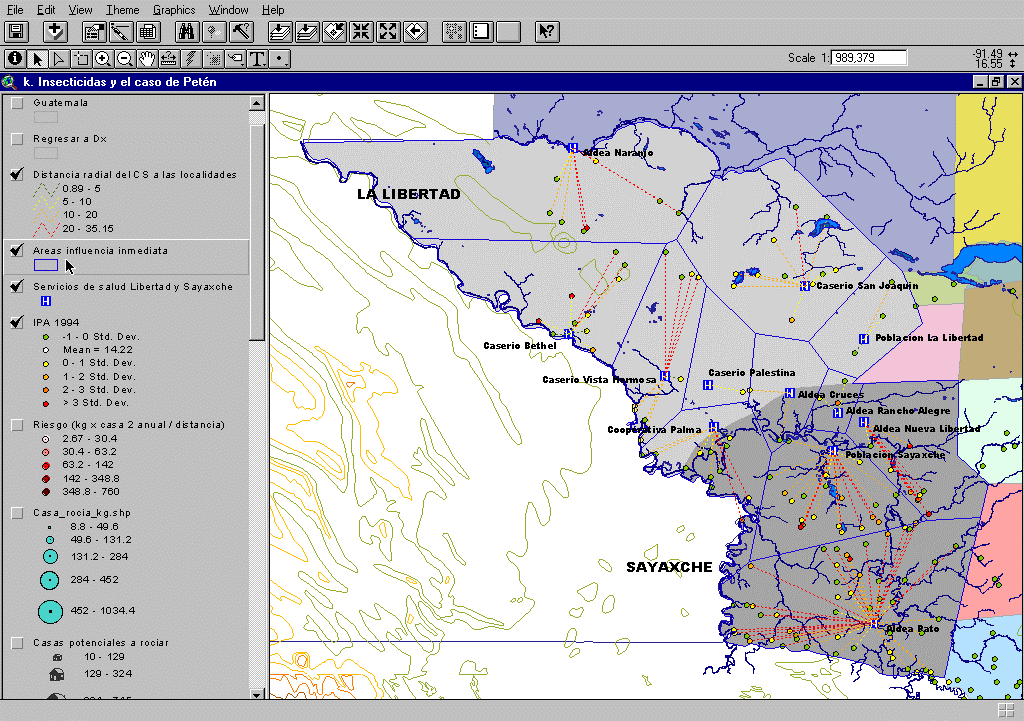

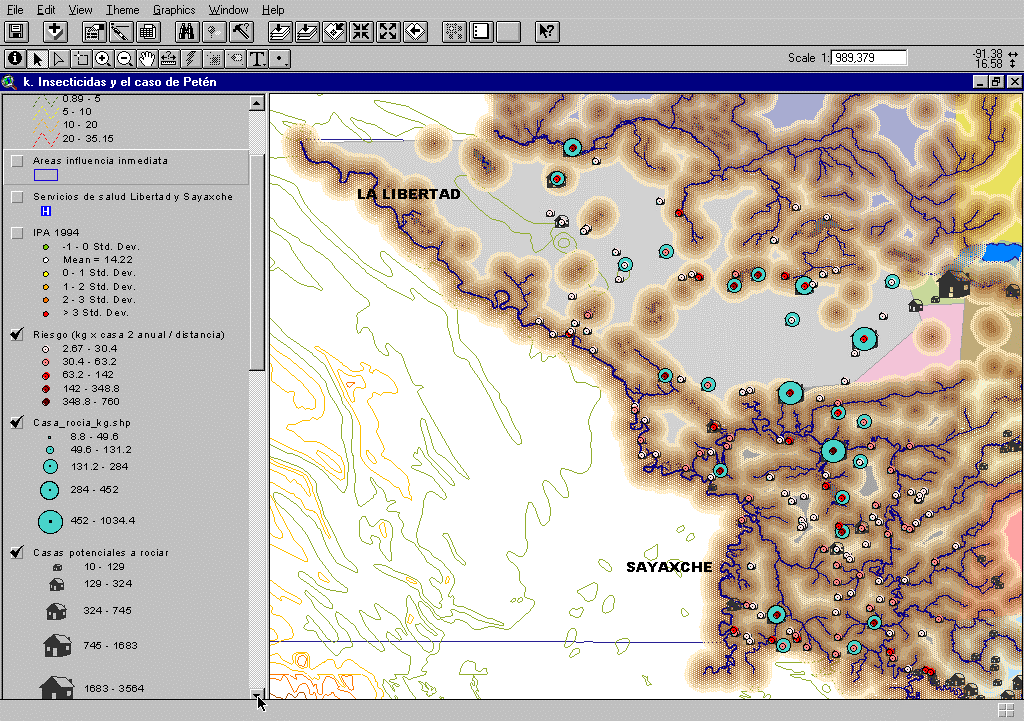

Project’s Web Page and Intranet functioning. Geographical Information System (GIS) accessible, containing digitized maps, malaria database for each participating country, geographical and environmental data relevant to malaria vector control. Electronic platform containing reports, documents, maps and database related to malaria control and exposure to DDT.

|

That the existing malaria reference centers in Mexico, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Panama, and Costa Rica are willing to integrate the regional Malaria Reference Center Network.

|

|

2. Strengthened regional institutional capacity to assess environmental and human exposure to DDT compounds and newly introduced pesticides |

Strengthened

national laboratory analysis capacity for chemical assessment and

monitoring. |

Results from inter-laboratory comparison exercises. Governments and local communities are aware of environmental and human contamination due to past exposure to DDT. |

That trained personnel can be retained to perform technical tasks. |

|

3. Final disposal of DDT stockpiles. |

The existing 135 tons of DDT stockpiles already identified in the region are disposed on a cost-effective basis. |

Report from disposal operations. |

That public opinion in receiving countries is such that no country can accept DDT waste. This seems unlikely to happen in all potential receiving countries in the immediate future. |

|

Components/Activities |

Objectively Verifiable Indicators |

Means of Verification (Monitoring focus) |

Critical Assumptions and Risks |

|

Component 1: Demonstration Projects and Dissemination.

|

- Demonstration projects of malaria control in each country. - Costs and feasibility of the new methods for malaria control evaluated in different countries and ecosystems. - Assessment of environment, biota and human exposure to DDT and other pesticides used for vector control. - Regional workshop on new approaches to malaria control. - Local meetings to facilitate community participation and training. - Implementation of Web and Intranet pages, and GIS. - 3 annual evaluation meetings. - Communication plan to promote public awareness on DDT hazards including printed educational materials and educational Campaign.

|

- Reports showing the results of each demonstration project in terms of technical and economical feasibility, environmental soundness and community participation. - Information on new approaches to malaria vector control and DDT compounds hazards to environment and human health available by the electronic platform and printed reports. - Web page with results of demonstration projects, national reports, technical studies, information on participating institutions. - GIS with geo-referred data on malaria control, DDT and insecticide use, malaria cases and population at risk; vector distribution, control interventions; environmental and ecological factors, health system coverage. - Reports from workshops and meetings. - Distribution of educational material. |

That the Demonstration Projects are well managed and the new techniques can be demonstrated to be environmentally sound, technically efficient, and cost effective. This risk is mitigated by the fact that the participating countries can already rely on a body of experience and expertise, and by the active involvement of PAHO’s experts in the execution of the project. |

Component 2: Strengthening of regional institutional capacities to control malaria without DDT.

|

- Technical manual on methodologies to be used in demonstration projects. - Final technical report on new strategies for malaria vector control - 8 national workshops and training courses for malaria and environment personnel on malaria vector entomology and ecology, integrated malaria vector control methods, field operations and community participation techniques. - Technical training and travel fellowships for technical personnel. - Strengthening of national reference centers for malaria control with personnel capacitated in risk assessment, community education and participation regarding to malaria control without DDT or other persistent pesticide. - Strengthening of laboratory analysis capacity. |

- Publication and distribution of manuals. - Publication and wide dissemination of report. - Reports of meetings and workshops. - Number of training and fellowships awarded. - System for monitoring and evaluating human and environmental exposure is implemented in the demonstration projects. - Annual reports of national reference centers. - Inter-laboratory quality control program for standardization of assessment procedures is put in place.

|

That the Governments of the participating countries have the will to support and encourage institutional strengthening in this field. This seems likely to be realized in light of the strong support and enthusiasm generated during the PDF-B phase. |

|

Component 3: Elimination of DDT stockpiles.

|

- Materials stored in leaking or inadequate containers are repacked in United Nations approved containers. - Shipment for final disposal of all 135 tons of DDT already identified. |

- Government warehouses are cleaned and all remaining materials are packed and stored in a safe manner. - Elimination of obsolete stockpiles scheduled and/or implemented.

|

That the stockpile elimination operations do not uncover great amount of yet unsuspected stockpiles. |

|

Component 4: Coordination and Management.

|

- 1 Project Coordinator. - 8 national technical coordinators to conduct the demonstration project activities. - 3 Steering Committee meetings - 3 regional technical meetings. - 3 annual reports of the demonstration projects. |

- Issuance of contracts. - Reports from meetings. |

That hiring of regional project coordinator and of national technical coordinators can proceed expeditiously. |

The phasing out of DDT in favor of alternative methods more benign to the environment and maintaining and improving human health in all aspects, remains a difficult, but necessary and worthwhile endeavor. For this to be successfully implemented in a region as vast and populated as Mexico and Central America, requires an approach of great scope and ambition. To combine the various malaria control activities of eight different countries will require a number of steps to accomplish. This proposed project will build on the past and present efforts of PAHO and other organizations in this regard, and could very well serve as a catalyst for further expansion and implementation of alternative malaria control methods, here and elsewhere.

The scope of this project is vast, but so is the disease. The gains that have been achieved with traditional malaria control practices are great, and these gains should not be compromised with short-sighted, short-term or unsustainable practices, that could introduce risks at levels other that those that are currently in effect. On the other hand, the known and insidious effects of DDT on humans and the biota are also not acceptable. To move away from DDT needs attention on an integrated and sustainable strategy to combat the disease on all fronts available for intervention. This project aims to achieve this for a large area, where smaller or disjunct efforts will, of necessity and design, have less impact. This project then very sensibly builds upon, and will strengthen local experience.

The results of an eventual successful adoption and implementation of cost effective and acceptable alternatives to DDT will not only be felt in the stated objectives alone, but will also support economic development of the region, as the burden of disease will be reduced. There is therefore a great responsibility upon the managers and all participants in this project to continue collaboration and communication through difficult times that undoubtedly will be experienced during this project. I therefore, have no hesitation to support this project design in all four of its components. There are however a number of areas where more attention can be given to, and these will be outlined below. In some cases these concerns might have been taken care of implicitly in the design process (logframe) or intention, and, if so addressed and understood, will therefore be moot. It is my opinion however, that the urgency of this project is such that improvements to the design can be made by the different levels of planning, management and supervision involved, without delaying the inception of this project.

TERMS OF REFERENCE

KEY ISSUES

1. Scientific and technical soundness of the project

Judged from the broad basis of the presentation of the project (Annex I), as well as the good detailed objective strategies of the demonstration projects provided (Annex VII), it is clear that this is the product of wide participation in preparation of this brief and outline.

- Although the role of agriculture is mentioned, the root cause analysis has one obvious short-coming. This is the potential of the concomitant use of pesticides, also intended for malaria control (most likely pyrethroids, but also others), to compromise sustainable use of such pesticides for malaria control, by contributing towards pesticide resistance. Although this was a root cause identified for the unstable use of DDT (i.e. the likelihood or resistance developing in mosquitoes to DDT), this is also valid for other pesticides. Agricultural use of alternatives was the cause of the multiple resistance development that led to the forced re-introduction of DDT in South Africa.

Resistance development was not as such identified as a possible cause for the re-introduction of DDT, due to the vectors becoming resistant to the alternatives. This concern should be incorporated into the objectives of the demonstration projects. This is especially the case for the demonstration projects in Honduras and Panama, where high agricultural use of pesticides is obvious from cotton and banana plantations near by. An effort should be made to incorporate the assessment of the agricultural use of pesticides close to the demonstration projects.

- In addition, activity 2.1.3 (Annex VI) should also include the training to determine resistance in mosquitoes, as a basic assessment tool to determine and protect the sustainability of alternatives.

- Overall, and both on a national and regional level, the management of resistance should receive attention so that the methods that show promise in the demonstration projects, can be implemented on a larger scale, during the follow-up of this project. Information gathering relevant to a possible regional policy on resistance management, should therefore be part of the objectives of this project. This could be included as one of the outcomes on the regional level.

- An additional capacity that would be very useful to acquire (or incorporated if available), is that of "Risk Assessment". The introduction of alternatives does have risks that are not negligible. The risk assessment process, that depend on data and information form the demonstration projects, will be a valuable addition to Component 3 of the logframe (Annex II) and "Expected Results" 1.5 (Annex VI). The logical consequence of risk assessment is risk management, an aspect that should be taken note of at this stage, but will likely play a much bigger role in large-scale implementation of alternative measures, following this project.

- It is probably implicit in the objectives of the data gathering that these will be collected on a comparable basis across all the demonstration projects. As it is likely that, as there are already such activities in each country, that there will be differences between them. Care should be taken to ensure comparability for further evaluation and possible risk assessment. Development of explicitly stated indicators of success (including aspects such as social acceptability of alternative measures) could be another benefit, if comparability of data gathering is achieved.

- Since a large portion of this work concerns social aspects, the relationship and attitudes of the people regarding malaria control will be crucial. It is therefore incumbent upon the project team members to concentrate on this aspect, as acceptability of alternative measures, which may include alteration of habits and activity patterns, be handled with care and sensitivity. The ethical component of some of the activities are important as well (e.g. monitoring of levels of pesticides in people, the administration of questionnaires, etc). To obtain formal ethical approval on appropriate levels does take time (and is therefore urgent) and this must be incorporated in the planning. I suggest that the obtaining of ethical approval be stated explicitly as one of the activities under 4.2.1 (Annex VI), so that it can be included under workplans. The basis for ethical approval will largely be common for all demonstration projects, and economy of effort will be obtained on this level.

- Depending on the development of the project, changes in the activity patterns and habits of people, may in itself have economic and or social advantages or disadvantages. These should be documented where possible, as it will have a bearing on the analysis of the cost effectiveness of these methods.

- Since one of the criteria mentioned at the outset of this project refers to cost effectiveness, the basis and assumptions for this is not explained. From activity 1.1.1 I assume that this is covered by the budget stated, but care must be taken that enough money will be available at the suitable stage of the project, to conduct this exercise. Since DDT is relatively cheap, cost effectiveness in this regard will have to include reference to difficult quantifiable measures of environmental health, the pollution of international waters, and others.

- The sites for the demonstration projects seem to be well chosen, judged from the information required.

- It is also probably implicit in the intent of this project, that the information needs of the implementers of malaria control measures be served by the GIS system that is to be developed. The experience gained from the various demonstration project (that are located in different geographic areas), can be used to predict areas where alternatives measures can be implemented (or not), provided the information needs for this is taken care of during the design and improvement of the GIS system.

- The time frame is quite short. Care should therefore be taken that the effect of seasonality does not result in the loss of one season, as the start-up phase of the project (when the demonstration projects are not yet active) might conceivably coincide with a transmission season.

- The South African experience has shown two things.

1) The implementation of alternative methods, when tested on a small scale, showed good promise. There were however, factors present on the larger scale, that were not apparent during the initial development and testing, which had serious consequences. It will not always be possible to foresee these factors or considerations, and implementation on a large scale will therefore need to take account of this during the planning. Deliberations on possible large scale considerations should already start during the final phase of this project, as the experience and insight from the people at the demonstration projects will be invaluable and should not be lost.

2) To manage the risk of possible failure of implementing alternatives, as well as to bolster the malaria control capabilities of the countries, the final phase of this project should deliberate on back-up mechanisms if necessary. From my own experience the malaria control officials on the ground are extremely protective of the people they protect. A fall-back strategy will be very useful to obtain their cooperation, as well as those from any other structures involved.

2. Global benefit / drawbacks

Although the direct benefits of this three year project will only have local benefits (these are demonstration projects), the results of this project will give a much better basis from which to determine the global benefit. This restriction is inherent in the intent and scope of this project. Defining the potential benefit that can be obtained by this project is therefore operative at this stage.

3. GEF context and goals

Within the GEF, the OP10 is the current and valid structure, as well as the draft POPs OP. Eventually the POPs OP will probably be the more applicable one. Care should however be taken by GEF that the continuity of the funding and support of the project scope and intent will not be negatively affected by any technical or administrative difficulties that might be experienced by such a changeover. Any positive support to this project emanating from the activation of the POPs OP should however, be encouraged where possible.

Otherwise the GEF context is clear. There seem to be little large scale risk, considering the scope of the project, but proposed habitat alterations or introductions of biological control mechanisms (such as mosquito-eating fish), especially if these could impact on natural areas (biodiversity) and processes, may pose a risk. These impacts should be included in a risk assessment. The impact of effective alternative measures (that are as yet not known) on the environment might be significant, if implemented on a larger scale. An Environmental Impact Assessment and a sustainability assessment might therefore be required at a later stage.

4. Regional context

This project is clearly regional, including all the countries.

5. Replicability of project in other areas

The results from this project will be replicable in other areas, but more likely on a project development or process basis, than in the details. Environmental, social, vector and parasite conditions vary across the world, but much can be learned from this project, on how to find solutions, and how to avoid the pitfalls.

6. Sustainability of the project

The sustainability of this project, given the level of funding and short time period, does not seem to be a problem. The implementation of the findings on a larger scale will be subject to the usual economic and social considerations, given the high level of importance of malaria, to both the region and its people. The advantage of this project design is that local knowledge will be incorporated. This aspect should not be neglected through the participatory approach inherent in the design. Failure to obtain the cooperation of the population is an obvious and stated risk (Annex II - local level).

SECONDARY ISSUES

1. Linkages to other focal areas

There might be linkages to biodiversity, as risks to biota in this species rich region will likely be present (either positive or negative) by implementation of alternative measures.

2. Linkages to other programs

These are stated in the documents provided. The Stockholm Convention would be another linkage, when it becomes effective. The Basel Convention would be an additional linkage for the disposal of DDT.

The South African Malaria Control Program has had great success in the development and implementation of a GIS in its combat of malaria over large areas. Contact with this group could be considered to aid in the development of the GIS system for this project.

3. Other beneficial or damaging environmental effects

The reduction of the release of DDT to the environment will be an obvious immediate benefit. The risks associated with alternative measures, such as other pesticides or habitat alteration needs to be taken into account. Alterations to water bodies might for instance increase the risk of flooding, or affect the water table. This is the reason to incorporate elements of both risk assessment and risk management in this project at some stage.

4. Degree of involvement of stakeholders

There is a high degree of involvement of stakeholders. This in itself creates of course its own complexity that needs good communications, as well as effective project management to maintain and derive the potential benefits. The major drawback of such a complex system of collaborative involvement will be unexpected delays.

The agricultural community should play a major role in this project.

5. Capacity-building

There are good and strong elements of capacity building in this project. If the other capacities mentioned above could also be included, it will further strengthen the project.

6. Innovativeness of the project

This project will build on the innovativeness of previous efforts as such. The project is also innovative in its scope and intent which spans eight countries.

Prof. Henk Bouwman

School for Environmental Sciences and Development

Potchefstroom University

P Bag X 6001

Potchefstroom 2520

South Africa

Tel +27 18 299 2377

Fax +27 18 2992370

Response to STAP Roster Review

The STAP Roster Expert’s comments are very supportive of this project in terms of its scope, objectives and design. Prof. Bouwman makes a number of valid suggestions and recommendations which, as he points out, do not necessarily imply changes in project design but will improve the chances of success of this project, if followed.

UNEP and PAHO agree with the comments of the reviewer and offer the following response to some of the issues raised.

a) Root cause analysis: The potential development of malaria vectors resistance to pyrethroids or other pesticides used in agriculture is a risk that has to be monitored. This concern will be incorporated into the objectives of the demonstration projects. The growing problem of vector’s resistance will require further investigations and investments towards resistance management procedures, preferably in coordination with agricultural programs promoting integrated pest management. Discussions are underway with DANIDA for further cooperation and funding.

DANIDA/PAHO’s PLAGSALUD project will provide the needed information on the agricultural use of pesticides in the demonstration project areas and their surroundings. The linkages between these two projects will facilitate the exchange of information related to types and quantities of pesticides used in the area. The need for assessment and identification of mosquito resistance to any of the newly introduced pesticides was discussed by the representatives of the participating countries during a meeting held in Mexico in the framework of the PDF-B, September 11-12 2001. We concur that the suggested “training to determine resistance in mosquitoes” should explicitly be included in the training workshops which will be conducted for the malaria control personnel involved in the project (item 2.1.3 Annex VI). We further concur that “gathering relevant information for a possible regional policy on resistance management” will be one important outcome at the regional level.

Risk Assessment: We agree on the importance of risk assessment related to the introduction of alternatives for malaria control. This is explicitly considered in item 1.5 (Annex VI) “Risk assessment of environmental and health effects of DDT, newly introduced pesticides, or other alternatives, in the areas and populations of demonstration projects”.

Comparability of data: It is implicit in Annex VI, items 1.4.1, 1.5.1, 1.5.2, that the data will be collected on a comparable basis across all the demonstration projects for further evaluation and possible risk assessment of the alternative techniques of malaria control.

Social aspects: We concur with the importance of social and ethical aspects related to the introduction of alternative measures which may require alteration of habits and activity patterns. An important asset for this project is the fact that DANIDA/PAHO’s PLAGSALUD program has been building community participation and public awareness on pesticides in Central America and Mexico since 1994. Most of the activities concerning social aspects will be developed in close collaboration with PLAGSALUD.

Cost effectiveness: Besides the assessment of environmental impacts and approval by the local communities, cost effectiveness is one fundamental aspect that will have to be evaluated as the project aims to develop replicable models of malaria control. UNEP and PAHO are aware of the complexity involved in this cost effectiveness due to the difficulty to quantify parameters related to effects of past use of DDT on environmental health, pollution of waters resources and others. On the positive side, the project will benefit from, and build upon, previous evaluation work, including work carried out in the participating countries.

Sustainability of the project: Special importance will be given to the incorporation of local knowledge and the participation of local community in all activities of the demonstration projects. Access to information and public participation at all stages of the demonstration projects, from workplan design to final evaluation, is the main strategy for the sustainability of this project.

Response to Implementing Agencies Comments

Comments were received from the World Bank. These comments are supportive, and only lament the lack of inclusion of some Caribbean Island States that could benefit from such a program. In view of the difficulty of the task proposed, however, an approach which initially focuses on a limited number of countries with experience of sub-regional collaboration on this particular issue is preferred.

WORK PROGRAM: COMMENTS FROM COUNCIL MEMBERS

(Reference to GEF/C 19/7 May 15-17, 2002)

Regional (Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama) Regional Program of Action and Demonstration Sustainable Alternatives to DDT for Malaria Vector Control in México and Central America (UNEP) GEF: $7.495 m; Total: $13.905 m

Comments from Germany:

The major project components will be the implementation of demonstration projects of vector control without DDT or other persistent pesticides, strengthening of national and local institutional capacity to control malaria without DDT, and the elimination of DDT stockpiles (135 tons from 8 countries).

It is important that the project focuses not only on DDT phasing-out but aims for non-persistent alternatives to malaria vector control. This aspect is well reflected in the project proposal.

The project activities related to strengthen national institutional capacity to control malaria without DDT focus mainly on supporting the laboratory infrastructure and DDT monitoring in the region. These are important activities, but capacity building activities should not be limited to these aspects only. It is well described in the outline of roots causes that e.g. one of the major problems is the illegal use of DDT specifically in areas of transboundary migrant farm workers and the availability of DDT at international level. Therefore, capacity building activities should include all relevant stakeholders (e.g. also migrant farmers, customs officers). This is an important aspect to achieve one of the main project objectives, i.e. avoiding the reintroduction of DDT, and will assist the countries to find their way to pesticide policy reforms, particularly the banning of persistent pesticides (refer to project proposal Section on “Monitoring, Evaluation and Dissemination”, para. 42. third and seventh bullet).

Disposal of existing DDT stocks is an important component of the project. With this the projects contributes to the implementation of the Stockholm Convention. However, the project component 3: “Elimination of DDT stockpiles” as described in the project proposal is too much end-of-pipe oriented. Activities in this field should be specified and linked to capacity building activities on preventive measures, e.g. the development of suitable measures to prevent the recurrence of obsolete pesticide accumulation, involvement of major stakeholders, particularly the chemical industry and the owners of the stockpiles, and the control of pesticides. This project component should be brought in consistency with the principal strategy currently under development in the PDF B/C “African Stockpile Program (ASP) Prevention and Disposal of Obsolete Pesticides from African Countries” (approved 12/14/01, IA World Bank).

Recommendation:

The proposed changes should be made during further planning steps and during project implementation.

Response to the comments of Germany

Overall, the comments of Germany are supportive to the implementation of this project designed to demonstrate the use of alternative methods of malaria vector control in Mexico and Central America without the use of DDT, to strengthen national and local institutional capacities to control malaria without DDT, and to eliminate existing DDT stockpiles. Specific response to Germany's remarks is provided herebelow.

Focus on persistent pesticides besides DDT

The alternative methodologies of malaria vector control which will be demonstrated in 9 different areas, under different environmental and social/economical conditions are indeed non dependable of any kind of persistent pesticides. The integrated approach to malaria vector control is based much more on environmental interventions, educational strategies, strengthening of public awareness, and effective cure of the malaria disease, than on spraying of insecticides. The spraying, when necessary, will be done with non-persistent pesticides as pyrethroids and organo-phosphorus compounds. The environment and the population of the demonstration project areas, as well as the malaria control service personnel, will be monitored regarding effects of past exposure to DDT and the newly introduced insecticides.

Inclusion of all relevant stakeholders as migrant farmers and customs officers.

One of the main strategies of this project is the participation of all stakeholders from the public sector and the civil society that will be involved in, and benefit from, the incorporation of integrated methods of malaria vector control. Capacity building strategies (training courses and workshops at local level, educational campaigns, collective environmental interventions for malaria vector control) and evaluation meetings will be held with participation of local groups, associations and institutions relevant not only to the implementation of the project activities, but to its sustainability in the future.

Local NGOs, institutions related to migrant farm workers, farmer associations, customs officers, and church groups, are among those who will be called to participate in these activities. A technical manual for the implementation of demonstration projects will address malaria control personnel, local farmers and migrant farm workers, providing technical information on the alternative strategies for malaria vector control.

At national level, special effort will be made to improve inter-sectoral collaboration, especially between the ministries of health, environment, agriculture and custom services, as the sustainability of practices introduced by the project will also depend on the monitoring system both for use and import of persistent pesticides. Special attention will be given at national level to policy recommendations and advocacy to legislation changes regarding persistent pesticides and DDT.

Measures to prevent the recurrence of obsolete pesticide accumulation

The problem of DDT stockpiles in Mexico and Central American countries, as identified during the PDF-B phase, is usually related to the lack of institutional concern, weak information and awareness on the subject, dispersed institutional responsibility, poor facilities, inadequate legislative and regulatory frameworks and weak enforcement. Consequently the problem has to be addressed by a concerted action on the issue, based on a multi-partner initiative to eliminate all obsolete stockpiles and help effectively prevent their re-emergence. The bases for action are awareness raising and training, detailed inventory, prevention programs, design of clean-up and disposal operations including environmental and health assessment, site clean-up programs, transport, and disposal operations.

Activities related to building capacity to prevent the recurrence of obsolete pesticide accumulation and promoting the involvement of major stakeholders, particularly the chemical industry and the owners of the stockpiles are part of the project component 3. Besides NGOs and international/regional organizations, the chemical industries and stockpile owners will be called to participate in the effort to update national inventories, in the evaluation of the problem of stockpiles at national and regional levels, and in the identification of existing capacities for elimination of persistent pesticides in the region.

All activities will be carried out according to the provisions of Rotterdam, Basel and Stockholm Conventions and experience from other projects and institutions will be considered to define the best methodologies to be used and the steps to be taken to ensure that impacts are properly mitigated.

Annex IV - Letters Of Endorsement from GEF Operational Focal Points

Major Problems |

Transboundary Elements |

Main Root Causes |

Types of Action |

Contamination of global ecosystems by DDT metabolites |

|

|

|

|

Unsustainable use of DDT for malaria vector control at global level |

|

|

|

|

Possibility of reintroducing the use of DDT for malaria control in countries where it has been phased-out |

|

|

|

|

Low institutional and community awareness about effects on human health and environment due to exposure to DDT |

|

|

|

Deficient national systems for monitoring environment and health |

|

|

|

Worsened human related conditions (lower quality of life, poverty, socio-economic decline) as a consequence of uncontrolled malaria disease and/or contamination with DDT metabolites |

|

|

|

Types of Action |

|

Technology Transfer (T) |

|

Awareness Raising (A) |

|

ANNEX VI – Detailed Description of Project Activities and Costs to the GEF

Project Component and objective |

Expected Results |

Activities |

Products |

Costs (total for 3 years in US$) |

|

Component # 1: Demonstration Projects and Dissemination

Objective: implement, evaluate and disseminate the alternative strategies of malaria vector control without DDT |

1.1.Documented demonstration projects of alternative malaria vector control without DDT or other persistent pesticides, in selected sites, using alternative techniques of malaria vector control. |

1.1.1. Implement, monitor and evaluate 9 malaria control demonstration projects (2 in Mexico and 1 in each of the 7 Central American countries), in areas of different ecological characteristics, public health and/or social-economic conditions. Document each experience and evaluate the cost effectiveness of the different methods.

|

9 demonstration projects implemented and evaluated.

|

$ 3,185,000

|

|

1.2. Community participation and educational strategies to build public awareness on new strategies for malaria vector control and the negative effects of DDT use. |

1.2.1. Organize and implement local meetings and workshops in each of the demonstration projects with participation of local health and environment professionals to emphasize and support local community participation in the process of alternative malaria vector control strategies, and to strengthen the activities of local health services. |

Local meetings with community participation and training on techniques for malaria vector control in each of the demonstration projects. |

$ 40,000

|

|

|

1.3. Strengthened regional institutional capacity to disseminate information related to malaria control methods that do not rely on DDT or other persistent pesticides. |

1.3.1. Develop a communication plan with participation of NGOs, and educational, environmental, and health national sectors, to support the evaluation of DDT and newly introduced pesticide effects on human health and environment, as well as to create awareness on DDT and integrated methods of malaria control of populations in risk areas. |

Communication plan to promote public awareness on DDT and educational campaign on new approaches of malaria control. |

$ 56,000

|

|

|

1.4. A region-wide information system on DDT and malaria control as a tool for gathering and disseminating data adequate to the needs of government in the decision-making process. |

1.4.1. Implement the web and intranet page designed during the PDF phase to facilitate the exchange of information and experiences among the participating countries, including collecting and validating existing regional information related to the project (documents, national reports, technical studies, participating institutions, regional reports); as well as the results of demonstration projects and analysis of DDT exposure. |

Information available through the Internet. Results and lessons learned from demonstration projects are shared among participating countries and other parts of the world. |

$ 50,000 |

|

|

1.5. Risk assessment of environmental and health effects of DDT, newly introduced pesticides, or other alternatives, in the areas and populations of demonstration project. |

1.5.1. Assessment of environmental and human exposure to DDT and newly introduced pesticides in the areas of demonstration projects. |

Results of assessment of environmental and human exposure to DDT and other pesticides used for malaria control are available. |

$ 120,000 |

|

|

15.2. Identify and map areas previously sprayed with DDT which are under risk of contamination by DDT compounds and have this information available in digitized format. |

Priority areas for risk evaluation are identified and mapped. |

$ 10,000

|

||

|

1.6. Demonstration projects are evaluated with community participation, results are available in CD and printed format, and disseminated through the electronic platform and Web Page. |

1.6.1. Support and facilitate community participation in demonstration projects, and disseminate the alternative techniques for malaria control without DDT. Organize 3 annual local meetings in each demonstration project area with the participation of community, local NGOs, local health services, environment and agriculture technicians to plan and evaluate the implemented activities. |

Annual reports of each demonstration project and organization of the information to be presented at the regional meeting |

$ 36,000

|

|

|

|

Subtotal for project component #1 |

|

$ 3,497,000 |

|

Project Component and objective |

Expected results |

Activities |

Products |

Costs (US$) |

|

Component # 2: Strengthening of national institutional capacities to control malaria

Objective: Strengthen national and local institutional capacities to control malaria with methods that do not rely on DDT or other environmentally persistent pesticides.

|

2.1. Strengthened national institutional capacities for malaria risk assessment, and malaria control without DDT.

|

2.1.1. Organize and provide support for a workshop in Mexico (Oaxaca) for national government authorities (decision making personnel) of health, environment, and agriculture ministries on the alternative strategies that will be applied in the demonstration projects, the assessment of DDT effects on human health and environment, and discussion of strategies for disposing the existing stockpiles of persistent pesticides and avoiding the formation of new ones. Involve the customs and farmers associations/groups of migrant farm workers to avoid the use, the accumulation and the import of pesticides. |

A two-day regional workshop for 4 representatives of each country (health, environment, and agriculture personnel). |

$ 30,000 |

|

2.1.2 Develop and print a technical manual addressing malaria control personnel, local farmers and migrant farm workers, providing technical information on alternative strategies for malaria vector control to be used under different ecological conditions. |

Technical manual of basic procedures for integrated malaria vector control without DDT. |

$ 15,000 |

||

|

2.1.3. Organize, provide supporting material, and implement a regional workshop for malaria control personnel, and representatives of environment and agriculture ministries of the eight participating countries to exchange experience and information on new approaches to malaria vector control, DDT residues assessment and alternatives for stockpile disposal. |

Regional technical workshop to exchange experience and information on new approaches to malaria vector control. |

$ 40,000

|

||

|

2.1.4. Organize and implement eight training courses for health and environment personnel as well as customs/import control personnel who will be involved in each of the demonstration projects on basic malaria epidemiology, malaria entomology (including determination of resistance in vectors), integrated malaria vector control methods, field operations, and community participation techniques, taking into consideration the different vectors, the endemic levels, and different environmental and social-economic conditions in each country. |

8 national training courses for qualified technicians from each country on Alternative Strategies for Malaria Vector Control and Field Operations. |

$ 32,000 |

||

|

2.1.5. Strengthen reference centers for malaria control in the participating countries, such as Mexico’s Centro de Investigaciones en Paludismo (CIP) and facilitate the regional exchange of information on malaria among laboratories and existing reference centers in the eight participating countries through the region-wide information network established by the project (described in item 1.2). |

Reference centers for malaria control are qualified, maintain recognized international standards and carry out information exchange. |

$ 120,000

|

||

|

2.1.6. Establish a malaria surveillance system and exchange of information on malaria control at regional level.

|

Malaria control programs of participating countries are integrated and sharing best experiences and lessons learned. |

$ 15,000 |

||

|

2.1.7. Short-term travel and local meetings for malaria control technicians to exchange experience on alternative integrated malaria vector control techniques. |

Malaria technicians prepared to use alternative integrated vector control techniques. |

$ 32,000 |

||

|

2.2. Strengthened analytical laboratory infrastructure and technical capacity regarding pesticide analysis, and assessment of environmental and human contamination. |

2. 2.1. Improve laboratory analysis capacity for chemical assessment in Mexico (Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí and CINVESTAV-Merida), Guatemala (Laboratorio Unificado de Control de Alimentos y Medicamentos – LUCAM), Nicaragua (CIRA-UNAM), Panama (Instituto Gorgas), Costa Rica (MAG) , El Salvador (Ministerio de Agricultura y Ganaderia), and Central Laboratory of Belize, as well as the exchange of information among them and other institutions. |

Equipped laboratories with technical capacity for chemical assessment of environmental contamination under international standards.

|

$ 480,000

|

|

|

2.2.2. Organize, provide support materials and implement a regional workshop for 2 laboratory technicians from each participating countries to establish mechanisms for standardization of assessment techniques, laboratory equipment, sampling techniques, georeferrenced data, interpretation of results, data base for GIS application. |

Workshop for 2 laboratory technicians of each participating country on laboratory analysis standardization. |

$ 30,000

|

||

|

2.2.3. Support the development of rapid inexpensive and easy to use assays for pesticides screening in human samples (based on ELISA or DELFIA methods) with collaboration of the Center on Environmental and Occupational Health Impact Assessment and Surveillance (Quebec, Canada). |

Rapid test validated. |

$ 50,000

|

||

|

2.2.4. Implement an inter-laboratory control program and capacity building on DDT compounds and other pesticides analyses in the participating countries to ensure that analytic results will be comparable across the participating countries and at international level through the participation and support of internationally recognized institutions of excellence. |

Training courses, manual for assessment of exposure to DDT and other newly introduced pesticides is implemented and available, travel fellowships for pesticide analysts. |

$ 100,000 |

||

|

2.2.5. Travel fellowships for qualified personnel for laboratory training for 8 technicians from Central American countries. |

Technicians with capacity to work under international standards. |

$ 50,000 |

||

|

2.3. GIS application providing data on DDT residues and new methods of malaria vector control in Mexico and Central America

|

2.3.1. GIS system to gather, organize and analyze the geographical and statistical components of malaria control and exposure to DDT and alternative pesticides used in the sub-region and in each demonstration project including standardized data on effects of exposure to DDT in Mexico and Central America, geo-referenced data on malaria control in the demonstration projects, spatial distribution of malaria vectors and populations at risk; distribution of control interventions; health system coverage, etc. |

A GIS application with maps, geographic and statistical data related to malaria control, DDT and alternative pesticides used in the sub-region and information on the demonstration projects. |

$ 200,000

|

|

|

2.3.2. Organize, prepare and print a substantive Final Report (CD and book format) to disseminate information on the results of the demonstration projects, information and maps of malaria risk areas, strategies for malaria control in different ecosystems without use of DDT, and analysis of effects of DDT and alternative pesticide exposure on human health and environment at the sub-regional level. |

Printed final report showing results of different strategies for malaria control without DDT under different ecosystems and social-economical conditions, illustrations in color, maps and information on malaria risk areas, data on effects of DDT exposure on human health and environment |

$ 50,000

|

||

|

Sub-total for project component #2 |

|

$ 1,244,000 |

||

Project component and objective |

Expected Results |

Activities |

Products |

Costs (US$) |

|

Component # 3: Elimination of DDT stockpiles

Objective: To eliminate the existing DDT stockpiles identified during PDF-B phase, repackage materials as required, and arrange for elimination of DDT on a cost effective basis. |

3. Existing DDT stockpiles repacked and/or disposed and mechanisms to avoid the creation of future stockpiles are initiated. |

3. 1. Update national inventories with participation of chemical industries and stockpile owners, evaluate the magnitude of the problem at regional level, and identify the existing capacity for elimination of persistent pesticides in the region.

3.2. Repackage in United Nations approved containers of all DDT or other persistent pesticides identified by the inventory.

3.3. Shipment and elimination of 135 tons of obsolete DDT already identified during PDF-B phase: Belize 13; Costa Rica 9; El Salvador 6; Guatemala 15; Mexico 87; Panama 5.

|

Existing DDT stockpiles repacked and/or disposed. |

$ 400,000

|

|

|

Sub-total for project component #3 |

|

$ 400,000 |

|

Project Component and objective |

Expected Results |

Activities |

Products |

Costs (US$) |

|

Component # 4: Coordination and Project Administration

Objective : Regional coordination of the project and related activities, and management of the project implementation. |

4.1. All project activities in the sub-region are coordinated and supervised; common objectives expressed by the countries are achieved. |

4.1.1. Hire and support a regional coordinator for the project during the period of 32 months.

|

Project activities are developed in a coordinated way and within the approved timetable.

|

$ 573,000 |

|

4.1.2. Hire and support a national coordinator in each participating country. |

Activities developed by the project are coordinated, documented, evaluated and made available by Web and printed material. |

$ 660,000 |

||

4.1.3. Organize and implement 3 steering committee meetings.

|

Report of steering committee meetings

|

$ 90,000

|

||

|

4.2. Operational Committee annual meetings for planning and evaluation of activities and approval of 3 annual reports . |

4.2.1. Organize and implement 3 regional meetings (Operational Committee) with the participation of government representatives on national health and environment, NGOs and community representatives to prepare workplan and discuss the results achieved with the project in each participating country |

Workplans and annual reports prepared and approved by the Operational Committee |

$ 120,000

|

|

|

|

4.2.2. Print 3 regional annual reports and prepare data for the electronic platform (Web page and GIS) on the demonstrative projects and all project activities. |

Results, geo-referred data, and digitized maps are organized and available through the electronic platform, CD format and printed report |

$ 15,000

|

|

|

4.3. Public awareness and community participation. |

4.3.3. Make available printed information and promote community meetings and workshops as part of each country's Communication Plan. |

Printed educational material and support for local meetings. |

Plagsalud

|

|

|

|

4.4.1. Support public awareness campaigns and events related to malaria control in schools located in malaria risk areas. |

Events related to schools located in malaria risk areas.

|

Plagsalud |

|

|

4.4.2. Support strategies to create a communication network among communities in malaria risk areas. |

Educational events, publication of leaflets, community meetings. |

Plagsalud |

||

|

Sub-total for project component #4 |

|

$ 1,458,000 |

||

|

SUB-TOTAL (project Costs)

|

$ 6,599,000 |

|||

|

Project Support Costs – PAHO (8%) |

$ 528,000 |

|||

|

Project preparation costs recovering |

$ 38,000 |

|||

|

PDF-B (already disbursed) |

$ 330,000 |

|||

|

TOTAL

|

$ 7,495,000 |

|||

Overall objective:

Develop a series of cost effective models for malaria vector control without the use of persistent pesticides which are applicable in different ecosystems and geographic locations with a participatory and integrated methodology, sensitive to the environment and the needs of different social groups, in common agreement with local governments and communities.

2. Specific objectives:

Promote the concept of disease prevention and the relation between environment and human health at the level of local communities ensuring that the activities to prevent and control malaria will improve local living conditions.

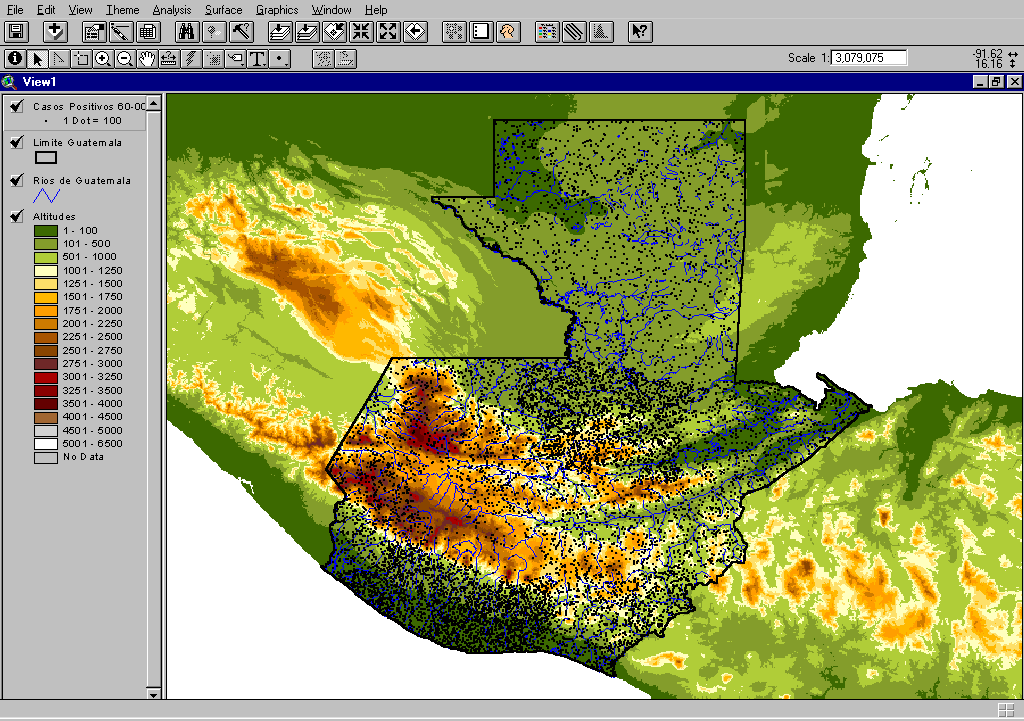

Identify the correlation between different malaria vectors and environmental factors as temperature, altitude, vegetation, land use, superficial water distribution, time of the day, etc.

Identify and implement adequate environmental interventions with community participation as removing green algae, moss and mud in water bodies to prevent mosquito breeding.

Monitor and register all activities implemented in each demonstration project in order to establish environmentally sound models which are replicable under similar environmental conditions.

Reduce the API (Annual Parasite Index = Number of malaria cases per 1000 population) of malaria fever among the stable population in each demonstration project site.

Reduce the percentage of positive malaria slides (Smear Positive Rate) in each demonstration site by at least 40%.

Reduce the number of people with gametocytes in blood film, meaning earlier diagnosis and less likelihood that mosquitoes will transmit the disease.

Reduce the amount of insecticides used, comparing data from the years prior to the project and at the end of the project.

Reduce mosquito-breeding sites within 500 meters of households (survey before and at the end of project).

Increase the accessibility to fast malaria diagnosis and treatment.

Reduce the length of time for obtaining a malaria diagnosis (time between having blood smear taken and the diagnosis).

Reduce the time people take to seek treatment (time between onset of malaria fever and person’s seeking diagnosis and treatment).

Decrease the number of persons with more than one episode of malaria per year (repeaters).

Decrease the number of households with more than one person affected with malaria per year.

Decrease the number of children under 5 years of age and between 5-9 with malaria.

Collect and register all activities related to malaria control implemented in each demonstration project area.

Identify and incorporate local knowledge on malaria control strategies.

Organize and strengthen community participation.

3. Criteria for the Selection of Areas for Carry out Demonstration Projects:

Malaria risk: Demonstration Projects will be carried out in areas where malaria is endemic and populations are under high risk of infection.

Access: The areas should be readily accessible throughout the year, in order to ensure that actions can be carried out without delays.

Environmental characteristics: Demonstration areas will have geographical/environmental characteristics which represent different types of climate (temperature and rainfall), topography (flat lands, low hills, mountains, etc), natural vegetation (mangroves, rainforest, etc.), and geographical location (coastal areas, interior regions, border zones, etc.).

Budget: Each demonstration project will receive government national and local budgetary allocations to complement the financial resources provided by GEF.

4. Detailed activities to be undertaken in each of the Demonstration Projects:

Step # 1: Diagnosis of the malaria problem

Identify incidence rates of malaria fever in the demonstration project area.

Identify type of Plasmodium most prevalent in the population.

Identify groups of people or families in the project area with the greatest number of malaria cases in the previous year.

Identify vectors responsible for the transmission of the disease in the locality.

Identify permanent and potential breeding sites of vectors in a radius of 500 meters of each house where malaria infection has occurred.

Identify periods of the day when there is greater vector density.

Identify potential health activists within the community (volunteers, midwifes, community leaders, etc.).

Identify health centers closest to the community.

Determine number and type of local health center personnel.

Inventory services available at local health center and/or hospitals (traditional diagnosis of malaria by microscopic analyses, availability of drugs, etc).

Identify criteria and treatment regimens used for suspected and/or diagnosed cases of malaria in the localities including: frequency of visit of malaria specialists for sampling and treatment of suspects. Determine if house spraying with insecticides was carried out; if there is participation of personnel outside the malaria service, etc.

Identify the length of time between collection of blood samples, diagnosis, and adequate treatment.

Identify historical use of insecticides in the area.

Inventory schools and churches in the area.

Identify sources of jobs or subsistence of local population.

Identify temporary migratory movements of people in the area.

Identify and quantify indigenous populations in the selected area.

Carry out fast tests for malaria diagnosis in international border areas.

Step # 2: Determination of environmental characterization of the area

Identify the climatic characteristics of the area (yearly distribution of rain and temperatures) and its relation to vector density and activity.

Identify the relation between altitude and the distribution of the malaria vector.

Identify the relation between malaria vector breeding sites and superficial water distribution.

Identify the relation between malaria vector breeding sites and the existing natural or introduced vegetation cover.

Identify the relation between malaria vector breeding sites and the location of agricultural fields.

Step #3: Implementation of environmental interventions

Mapping of vector breeding site locations identifying species of Anopheles mosquito present.

Implementation of breeding site clean-up with community participation by removing garbage and other materials that could facilitate the breeding of mosquito larvae.

Elimination of green algae, moss and mud in creeks to prevent mosquito breeding (with community participation, once a month).

Biological control of breeding sites (optional according to each country experience and decision). Available strategies are:

Bacillus thurigiensis and/or Bacillus sphaericus (positive experience in Guatemala, Nicaragua and Honduras);

Larvae eating fish (Honduras and Guatemala);

Use of alcohol to control larvae (Mexico);

Natural repellents produced from leaves of Neem tree (Guatemala).

Drainage of temporary deposits of stagnated water and cleaning of water canals

Spraying of non-persistent pesticides or oil components on water surfaces not subject to drainage to interrupt larvae breeding.

Collection (with local community involvement) of organic, recyclable and non-recyclable trash and facilitating its adequate disposal.

Promotion of domestic hygiene practices among the local population.

Spraying non-persistent insecticides in households where malaria has been persistent or had occurred in the last year. Determination of correct adjustments of volume and time in relation to specific vectors present at the site (A. pseudopunctipennis or A. albimanus).

Promotion of the use of physical barriers and personal protection such as bednets and repellents.

Step #4: Treatment of malaria

Different options for malaria treatment are available and may be incorporated in the practices employed in each demonstration project, i.e., “single dose” (sequence of 3 consecutive monthly doses and 3 months of rest is repeated during 3 years), “radical cure” in 3 days, “radical cure” in 5 days, or “radical cure” in 14 days.

Step #5: Organization of Community Participation

Organize working teams for diagnostic activities and environmental interventions.

Organize and implement meetings, workshops, training courses, etc. with local community in each demonstration area.

Identify and promote training on malaria control strategies for local leaders.

Build capacity of local volunteers to promote preventive strategies of malaria control among local people.

Step #6: Collection and analysis of data, and dissemination of results

Identify people in the community and local health service centers to be trained in malaria diagnosis, identification of vectors, and identification of breeding sites.

Identify and locate by GPS the existing malaria vector breeding sites.

Determine the number of persons living in each demonstration area.

Identify the main epidemiological variables including: migratory movements of workers, type of malaria vector present, and time of the year or season of great concentration of the vector (relation to climate), susceptibility of the vector to the insecticides utilized in vector control, immunological response of the population, degree of endemicity and distribution of different strains of the parasite, cultural behavior of the indigenous population, and socio-economic activities of the region.

Identify number of microscopes available in the area for rapid diagnostic tests.

Identify persons who do not respond to the applied treatment.

Complete provided forms with field information on environmental conditions and malaria vectors.

Register all implemented activities and results obtained related to the integrated strategies for preventing and controlling malaria.

Organize the geo-referenced database (with use of GPS) and provide data for the GIS.

Integrate the data to the National and Regional Information System (WebPage and GIS).

Monitor and register the impacts of the interventions.

Monitor and register all costs related to the malaria control interventions in each demonstration project.

|

Place |

Location and Altitude |

Environmental Characteristics |

Land Use |

Vectors Anopheles |

ParasitePlasmodium |

Existing Health system |

Community Participation |

Notes |

BELIZEDistricts of Toledo, Cayo and Stann Creek

20,000 inhabitants under risk Approx. 10,000 km2 |

89W/16.5N <600 meters above sea level |

Low and swampy Atlantic coast with lagoons, hills and valleys in the southern portion uplands. Subtropical climate, mean temperatures between 23C in December to 29C in July. Annual rainfall around 2000 mm, with a dry season from February to May, rain season from June to December. Natural vegetation: mangroves, swamp forests close to rivers, parklike savanna in the coastal plains. |

Agriculture: rice, citrus fruits (orange and grapefruit), bananas. |

A. albimanus (predominant) A.vestitipennis A. darlingy |

P. vivax (99%) P. falciparum

|

Good system, currently with foreign medical doctors participating in a program of health assistance for the villages. |

Good |

Immigrant workers from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, and villages of refugees from El Salvador (UN); good terrestrial communications. |

COSTA RICAHuetar Atlantica (Cantón Talamanca) 30,000 inhabitants under risk Area: 2,809 km² |

84W/9N <1000 meters above sea level |

Mountains flanks and tablelands made fertile by volcanic ash extending to swampy coastal plains; hot and humid climate (27C) on the coast, cooler with altitude; moist northeast rains can bring rain throughout the year (3200mm); Tropical broadleaf forests cover most of the area, while palms and mangroves thrive in the coastal plain. |

Agriculture: bananas and organic cocoa. |

A. albimanus (predominant) |

P. vivax (100%) |

Good coverage of medical services |

Well established and active. |

Easy access, immigration from Panama and Nicaragua, indigenous area (some with difficult access) and other ethnic communities |

EL SALVADORSonsonate La Paz, Usulutan 120,000 inhabitants under risk |

90W/14N <500 meters above sea level |

Pacific lowlands and coastal hills; tropical climate (hot and humid) temperature varies with altitude (annual average 23C), hottest months are April and May, rainy season from May to November (1800 mm/year). Tropical grassland and deciduous broadleaf forest. |

Agriculture: coffee, and sugarcane |

A. albimanus |

P. vivax |